Welcome to the flavorful world of Texas barbecue, where the rich tapestry of Hispanic heritage meets the art of smoked, grilled meat. At Davila’s BBQ, the celebration is not just about the mouthwatering dishes served, but also the vibrant stories and traditions that have shaped Texan cuisine for generations.

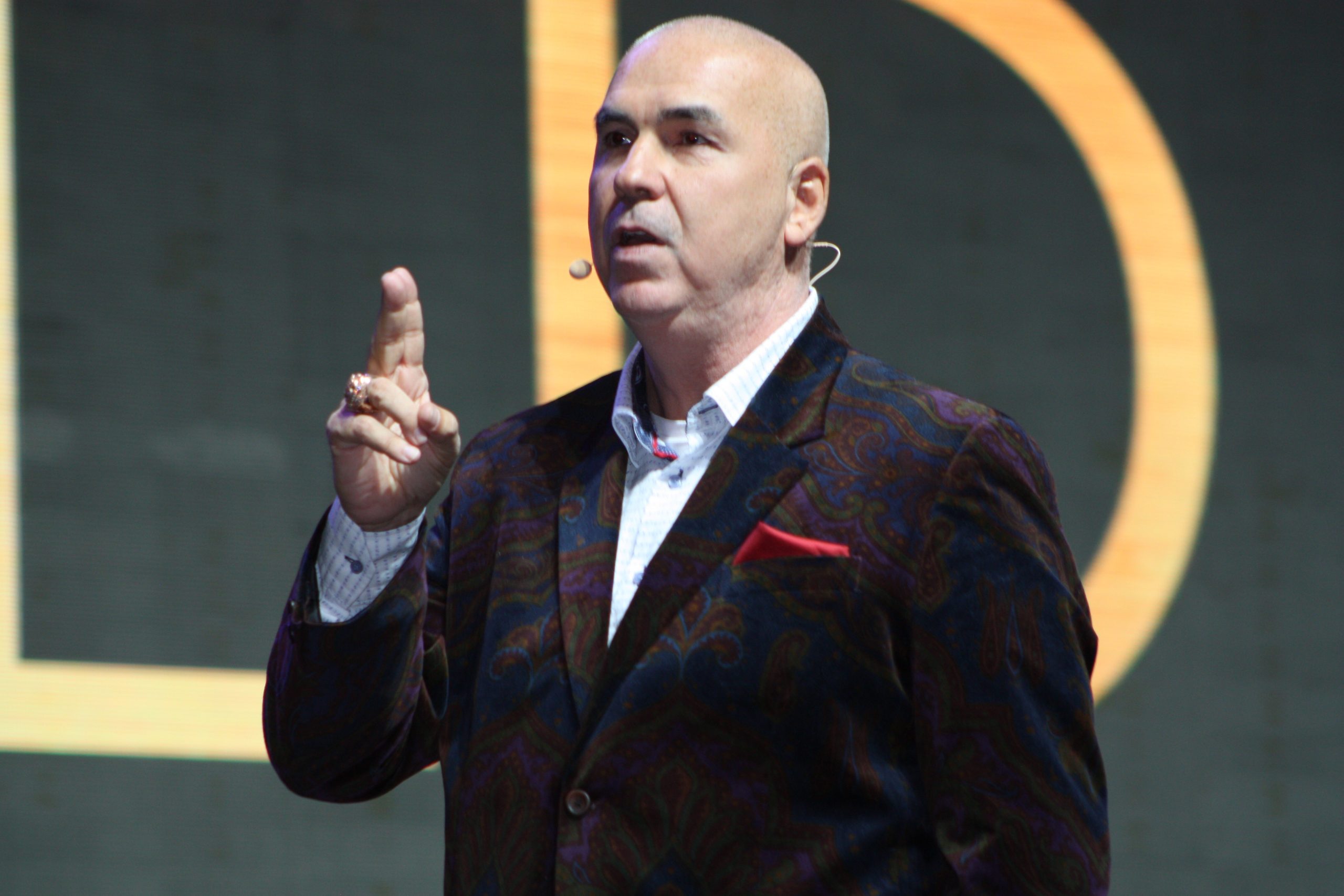

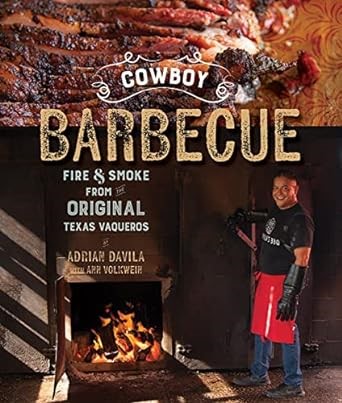

Adrian Davila, a third-generation pitmaster, takes patrons on a journey through time, taste, and culture in his new book, Cowboy Barbecue, which honors the traditions of Latin American and Texan cooking while taking inspiration from the vaquero lifestyle. In commemoration of Hispanic Heritage Month, read on for Davila’s exploration of the fusion of flavors and histories that define the culinary landscape in this rich region.

A Legacy of Excellence

To truly understand the essence of Davila’s BBQ, it is necessary to trace the family’s roots. The journey starts in Avila, Spain, proceeds onward to present-day Peru, and then heads northward into the lands of northern Mexico. Like many others, the Davila family’s story is one of adaptation, resourcefulness, and a love for the land that would ultimately shape their culinary traditions.

Adrian Davila’s history is deeply embedded in Mexican-American ethnicity and the enduring work ethic of his grandfather and father. The art of barbecue was learned by Davila and his family members at a young age, and these skills continue to be practiced daily. Food is more than nourishment; it is the story of culture.

The Vaquero Way

The vaqueros, often considered the original cowboys, were pivotal in shaping Texas’ lauded cuisine. These cattle herders on horseback were known for their nomadic lifestyle, constantly on the move as they roamed the expansive Texan and Mexican landscapes. Ingredients had to be portable, and they relied on simple staples like tortillas, beans, and rice. The vaqueros cooked over open fires, infusing their dishes with the aromatic flavors of mesquite wood.

Vaqueros were shepherds, herding their cattle from grassland to fresh grassland. With no home base, these men of the land were married to the cows and prioritized them in all their actions. The original vaqueros had a fiercely independent spirit and a profound connection to the cattle and the land itself that is still found in present-day vaqueros.

Modern dishes like mesquite-smoked lamb ribs echo the ingenuity of the vaqueros. These pioneering cowboys were the original pitmasters, employing slow-smoking techniques and infusing local ingredients with the vibrant, intense notes of the Iberian Peninsula. They used the ingredients that were available to them, adapting each to their cooking techniques and bringing them to their tables. When they weren’t roasting meat while on the move, these Spanish immigrants drew together cuisine from an often unforgiving land. Ingredients like nopales (cactus paddles), tripas, and blood sausage were common.

The vaqueros cooked over an open fire using the mesquite wood they’d gathered. A designated forager and trapper would bring them the occasional turkey, quail, rabbit, dove, or snake, and they might occasionally be allotted a calf by the cattle owners. But eating beef, pork, or chicken was often reserved for celebratory asados (open-fire barbecues) and special occasions.

The vaquero way of cooking is all about using what is readily available and being resourceful. It is about respecting the land and its gifts.

Can It

It wasn’t until 1809 that food started to be canned, so ingredients like beans, flour, masa, and rice became fast favorites to stock up when vaqueros purchased foodstuffs before long rides. To this day, these staples form the center of dinner tables all over the region.

Preserving Traditions

One of the most profound lessons learned on this culinary journey is the importance of preserving traditions. As the modern food industry has evolved, it has become easy to lose touch with the origins of meals.

Traditions run deep up in the mountains. Whether it was for a funeral feast or a marriage celebration, nothing was wasted, not even a single drop of blood. For example, women used the meat from a funeral pig’s head, cheek, and jowls to make tamales, while the skin was used to make chicharrones and the stomach was stuffed with rice and organ meat. The main body, of course, was barbecued, and the legs were cooked underground. Food was and is central to gatherings, with everyone participating in the preparations, and many of these food traditions remain today.

Conclusion

As Hispanic Heritage Month is observed, the Davila family encourages Hispanic Americans across the country to reconnect to their roots. Trace your family lineage, ask your grandparents questions, and write down family recipes. Food traditions are too easily lost, and it is our duty to preserve them for generations to come. Not only do food traditions make for meaningful gatherings, but they help us better understand our past and chart our future. Journeys through time and tradition allow each dish to tell a story, and each bite is a taste of heritage. Can you smell the mesquite?